Viking activity in the Iberian peninsula seems to have begun around the mid-ninth century as an extension of Viking raids on and establishment of bases in Frankia in the earlier ninth century. While connections between the Norse and Eastern Islamic lands were well-established, particularly involving the Rus' along the Volga and around the Caspian Sea, relations with the Western edge of Islam were more sporadic and haphazard. Although Vikings may have over-wintered in Iberia, no evidence has been found for trading or settlement. Indeed, the Iberian peninsula may not have offered particularly wealthy targets, in the ninth to tenth centuries. Sporadic raiding continued until the end of the Viking Age. Our knowledge of Vikings in Iberia is mainly based on written accounts. There are archaeological findings of what may have been anchors of Viking ships, and some shapes of mounds by riversides look similar to the Norse longphorts in Ireland. These may have been ports or docks for Viking longships.

Compared with the rest of Western Europe, the Iberian Peninsula seems to have been little affected by Viking activity, either in the Christian north or the Muslim south. In some of their raids on Spain, the Vikings were crushed either by the Kingdom of Asturias or the Emirate armies. Our knowledge of Vikings in Iberia is mainly based on written accounts, many of which are much later than the events they purport to describe, and often also ambiguous about the origins or ethnicity of the raiders they mention. A little possible archaeological evidence has come to light, but research in this area is ongoing. Viking activity in the Iberian peninsula seems to have begun around the mid-ninth century as an extension of their raids on and establishment of bases in Frankia in the earlier ninth century, but although Vikings may have over-wintered there, there is as yet no evidence for trading or settlement. The most prominent and probably most significant event was a raid in 844, when Vikings entered the Garonne and attacked Galicia and Asturias. When the Vikings attacked A Coruña they were met by the army of King Ramiro I and were heavily defeated. Many of the Vikings' casualties were caused by the Galicians' ballistas powerful torsion-powered projectile weapons that looked rather like giant crossbows. 70 of the Vikings' longships were captured on the beach and burned. They then proceeded south, raiding Lisbon and Seville. This Viking raid on Seville seems to have constituted a significant attack. 859–861 AD saw another spate of Viking raids, apparently by a single group. Despite some elaborate tales in late sources, little is known for sure about these attacks. After unsuccessful raids on both northern Iberia and al-Andalus, the Vikings seem also to have raided other Mediterranean targets. Evidence for Viking activity in Iberia vanishes after the 860s, until the 960s-70s, when a range of sources including Dudo of Saint-Quentin, Ibn Ḥayyān, and Ibn Idhārī, along with a number of charters from Christian Iberia, while individually unreliable, together afford convincing evidence for Viking raids on Iberia in the 960s and 970s. Tenth- or eleventh-century fragments of mouse bone found in Madeira, along with mitocondrial DNA of Madeiran mice, suggests that Vikings also came to Madeira (bringing mice with them), long before the island was colonised by Portugal. Quite extensive evidence for minor Viking raids in Iberia continues for the early eleventh century in later narratives (including some Icelandic sagas) and in northern Iberian charters. As the Viking Age drew to a close, Scandinavians and Normans continued to have opportunities to visit and raid Iberia while on their way to the Holy Land for pilgrimage or crusade, or in connection with Norman conquests in the Mediterranean. Key examples in the saga literature are Sigurðr Jórsalafari (king of Norway 1103-1130) and Røgnvaldr kali Kolsson (d. 1158).

The Viking raid on Seville, then part of the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba, took place in 844. After raiding the coasts of Spain and Portugal, a Viking fleet arrived in Seville through the Guadalquivir on 25 September, and took the city on 1 or 3 October. The Vikings pillaged the city and the surrounding areas. Emir Abd ar-Rahman II of Córdoba mobilised and sent a large force against the Vikings under the command of the hajib (chief-minister) Isa ibn Shuhayd. After a series of indecisive engagements, the Muslim army defeated the Vikings on either 11 or 17 November. Seville was retaken, and the remnants of the Vikings fled Spain. After the raid, the Muslims raised new troops and built more ships and other military equipment to protect the coast. The quick military response in 844 and the subsequent defensive improvements discouraged further attacks by the Vikings. Historians such as Hugh N. Kennedy and Neil Price contrast the rapid Muslim response during the 844 raid, as well as the organization of long-term defences, with the weak responses by the contemporary Carolingians and Anglo-Saxons against the Vikings.

The Viking fleet, composed of allies of Hastein and Björn Ironside, sailed from their base at Noirmoutier on the Loire river estuary in Francia. Prior to attacking Seville, it was seen near the coast of France and on French rivers (the Seine, the Loire, and the Garonne). They plundered Asturias, under the rule of the Christian King Ramiro I, but suffered heavy losses at A Coruña and were defeated by Ramiro at the Tower of Hercules. Next, they sailed southward and plundered the Atlantic coast. They took the Muslim city of Lisbon in August or September of 844 and occupied it for 13 days, during which time they engaged in skirmishes with the Muslims. The governor of Lisbon, Wahballah ibn Hazm, wrote about the attack to Emir Abd ar-Rahman II of Córdoba, who was the overall leader of Muslims in Spain. After leaving Lisbon, they sailed further south and raided the Spanish towns of Cadiz, Medina Sidonia, and Algeciras, and possibly the Abbasid-controlled town of Asilah in Morocco.

On 25 September, the Vikings arrived near Seville after sailing up the Guadalquivir. They set up their base on Isla Menor, a defensible island on the Guadalquivir Marshes. On 29 September, local Muslim forces marched against the Vikings but were defeated. The Vikings took Seville by storm on 1 or 3 October after a brief siege and heavy fighting. They looted and pillaged the city, and, according to Muslim historians, gave its inhabitants the "terrors of imprisonment or death" and spared "not even the beasts of burden". Although the unwalled city of Seville was taken, its citadel remained in Muslim hands. The Vikings tried but failed to burn the city's recently-built great mosque.

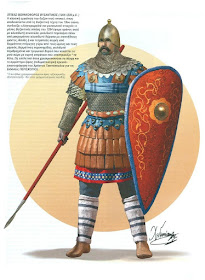

When he heard about the fall of Seville, Abd ar-Rahman II mobilized his forces under the leadership of his hajib, Isa ibn Shuhayd. He summoned nearby governors to gather their men. They assembled in Córdoba, and then marched to Axarafe, a hill near Seville, where Isa ibn Shuhayd set up his headquarters. A contingent led by Musa ibn Musa al-Qasi, the leader of the semi-independent Banu Qasi principality to the north, joined this army despite Musa ibn Musa's political rivalry with Abd ar-Rahman, and played an important part in the campaign. In the following days, the two sides clashed multiple times, with varying results. Finally the Muslims won a major victory on 11 or 17 November at Talyata. According to Muslim sources, 500 to 1000 Vikings were killed and 30 Viking ships were destroyed. The Muslims made use of Greek Fire. The Muslims also reported that the commanders of the Vikings were killed and at least 400 were captured many of whom were hanged from the palm-trees of Talyata. The remaining Vikings retreated to their vessels and sailed downriver while the inhabitants of the surrounding countryside pelted them with stones. Soon, the Vikings offered to trade the plunder and prisoners they had taken in exchange for clothes, food, and unhindered downriver journey. After that, they rejoined the rest of the fleet on the coast. The weakened fleet, pursued by Abd ar-Rahman's ships, left the Iberian Peninsula after a brief raid in the Algarve.

The city of Seville and its suburbs were left in ruins. The destruction caused by the Viking raiders terrified the people of Al-Andalus. Abd ar-Rahman ordered new measures to guard against further raids. He established a naval arsenal in Seville and built walls around the city and other settlements. Ships and weaponry were made, sailors and troops were raised, and messenger networks were established to spread information about future attacks. These measures were successful in frustrating later Viking raids in 859 and 966. Most of the Vikings sailed back to Francia, and their defeat by the Andalusian army might have discouraged them from attacking the Iberian Peninsula again. The following year, the Vikings sent an embassy to the court of Abd ar-Rahman, who then sent the poet Yahya ibn al-Hakam (nicknamed Al-Ghazal, "the Gazelle") as an ambassador to the Vikings. Later Islamic sources report that some of the raiders remained and settled in the area, converted to Islam, and became cheese traders.

Evidence for Viking activity in Iberia after 861 is sparse for nearly a century: a range of sources including Dudo of Saint-Quentin, Ibn Ḥayyān, and Ibn Idhārī, along with a number of charters from Christian Iberia, together afford convincing evidence for Viking raids on Iberia in the 960s and 970s. The Chronicle of Sampiro and a number of later sources portray a raid in 968 led by one Gundered: a fleet of a hundred ships of Norsemen and Flemings arrives at the port of Iuncaria, intending to pillage Iria, but the Vikings are met at Fornelos by the armies of Bishop Sisnando Menéndez, who is killed in the battle. After three years devastating and pillaging the land, they are defeated at the Cebreiro mountains by one Gonzalo Sánchez, either a Galician count, Gonzalo Sánchez, or, according to some authors, as William Sánchez of Gascony. Bishop Sisnando was responsible for the fortification of Santiago de Compostela, allegedly against the raids of Norse, Flemings, and other enemies who uses to raid the lands and shores of Galicia. Several Galician charters of later decades relate the destruction of monasteries and the suffering of the people as "dies Lordemanorum" ("day of the Northmen"); in particular one charter dated in 996 uses the location of an ancient fortress of the Norse, in the south bank of the Ulla river, as a landmark. According to Ibn Idhārī, in 966 Lisbon was again raided by the Norse, this time with a fleet of 28 ships, but they were successfully repulsed. He recounts further raids in Al-Andalus, in a series of annalistic asides to narratives of events in Córdoba, for 971-72; these records chime with a note in the textually related, and not necessarily reliable, Anales Complutenses and the first group of the Anales Toledanos saying that Vikings attacked Campos (Santiago or to the Campos Goticos in the province of Leon) in 970.

Around 860, Ermentarius of Noirmoutier and the Annals of St-Bertin provide contemporary evidence for Vikings based in Frankia proceeding to Iberia and thence to Italy. Three or four eleventh-century Swedish Runestones mention Italy, memorialising warriors who died in 'Langbarðaland', the Old Norse name for southern Italy (Langobardia Minor). It seems clear that rather than being Normans, these men were Varangian mercenaries fighting for Byzantium. Varangians may first have been deployed as mercenaries in Italy against the Arabs as early as 936. Later several Anglo-Danish and Norwegian nobles participated in the Norman conquest of southern Italy. Harald Sigurdsson (c. 1015 –1066), given the epithet Hardrada ("stern counsel" or "hard ruler") in the sagas, was King of Norway (as Harald III) from 1046 to 1066. In addition, he unsuccessfully claimed the Danish throne until 1064 and the English throne in 1066. Before becoming king, Harald had spent around fifteen years in exile as a mercenary and military commander in Kievan Rus' and of the Varangian Guard in the Byzantine Empire. In 1038, Harald joined the Byzantines in their expedition to Sicily, in George Maniakes's (the sagas' "Gyrge") attempt to reconquer the island from the Muslim Saracens, who had established the Emirate of Sicily on the island. During the campaign, Harald fought alongside Norman mercenaries such as William Iron Arm. According to Snorri Sturluson, Harald captured four towns on Sicily. In 1041, when the Byzantine expedition to Sicily was over, a Lombard - Norman revolt erupted in southern Italy, and Harald led the Varangian Guard in multiple battles. Harald fought with the Catepan of Italy, Michael Dokeianos with initial success, but the Normans, led by their former ally William Iron Arm, defeated the Byzantines in the Battle of Olivento in March, and in the Battle of Montemaggiore in May. After the defeat, Harald and the Varangian Guard were called back to Constantinople, following Maniakes' imprisonment by the emperor and the onset of other more pressing issues. Harald and the Varangians were thereafter sent to fight in the southeastern European frontier as the Balkan peninsula in Bulgaria, where they arrived in late 1041. There, he fought in the army of Emperor Michael IV in the Battle of Ostrovo of the 1041 campaign against the Bulgarian uprising led by Peter Delyan, which later gained Harald the nickname the "Bulgar-burner" (Bolgara brennir) by his skald. Edgar the Ætheling, who left England in 1086, went there, Jarl Erling Skakke won his nickname after a battle against Arabs in Sicily. On the other hand, many Anglo-Danish rebels fleeing William the Conqueror, joined the Byzantines in their struggle against Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, in Southern Italy.

Björn Ironside was a historical Swedish Viking chief who also figures in late sources as a son of Ragnar Lodbrok and a legendary king of Sweden. He lived in the 9th century, being securely dated between 855 and 858. Björn Ironside is said to have been the first ruler of the Swedish Munsö dynasty. In the early 18th century, a barrow on the island of Munsö was claimed by antiquarians to be Björn Järnsidas hög or Björn Ironside's barrow. Medieval sources refer to Björn Ironside's potential sons and grandsons, including Erik Björnsson and Björn at Haugi. His descendants in the male line supposedly ruled over the Swedes until c. 1060. The complicity of Björn in all this is unclear. However, a number of Frankish, Arab and Irish sources mention a large Viking raid into the Mediterranean in 859-861 where he was supposedly involved. After raiding down the Iberian coast and fighting their way through Gibraltar, the Norsemen pillaged the south of France, where the fleet stayed over winter, before landing in Italy where they captured the city of Pisa. Flush with this victory and others around the Mediterranean (including in Sicily and North Africa) during the Mediterranean expedition, the Vikings are recorded to have lost 40 ships to a storm. They returned to the Straits of Gibraltar and, at the coast of Medina-Sidonia, lost 2 ships to fire catapults in a surprise raid by Andalusian forces, leaving only 20 ships intact. The remnants of the fleet came back to French waters in 862. Björn Ironside was the leader of the expedition according to the later chronicle of William of Jumièges. The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland say that two sons of Ragnall mac Albdan (Ragnar Lodbrok?), a chief who has been expelled from Lochlann by his brothers and stayed in the Orkney Islands, headed the enterprise. William of Jumièges refers to Björn as Bier Costae ferreae (Ironside) who was Lotbroci regis filio(son of King Lodbrok). William's circumstantial account of the Mediterranean expedition centers around Björn's foster-father Hastein. The two Vikings conducted many (mostly successful) raids in France. Later on Hastein got the idea to make Björn the new Roman Emperor and led a large Viking raid into the Mediterranean together with his protegée. They proceeded inland to the town of Luna, which they believed to be Rome at the time, but were unable to breach the town walls. To gain entry a tricky plan was devised: Hastein sent messengers to the bishop to say that, being deathly ill, he had a deathbed conversion and wished to receive Christian sacraments and/or to be buried on consecrated ground within their church. He was brought into the chapel with a small honor guard, then surprised the dismayed clerics by leaping from his stretcher. The Viking party then hacked its way to the town gates, which were promptly opened letting the rest of the army in. When they realised that Luna was not Rome, Björn and Hastein wished to invest this city but changed their minds when they heard that the Romans were well prepared for defense. After returning to West Europe, the two men parted company. Björn was shipwrecked at the English coast and barely survived. He then went to Frisia where he died.There are some historical problems with this account. Hastein appears in the contemporary sources later than Björn and could hardly, for chronological reasons, be his foster-father. Moreover, Luni is known to have been plundered by Saracens rather than by Vikings.

Πηγή : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Björn_Ironside

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viking_expansion

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vikings_in_Iberia

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harald_Hardrada

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viking_raid_on_Seville

Compared with the rest of Western Europe, the Iberian Peninsula seems to have been little affected by Viking activity, either in the Christian north or the Muslim south. In some of their raids on Spain, the Vikings were crushed either by the Kingdom of Asturias or the Emirate armies. Our knowledge of Vikings in Iberia is mainly based on written accounts, many of which are much later than the events they purport to describe, and often also ambiguous about the origins or ethnicity of the raiders they mention. A little possible archaeological evidence has come to light, but research in this area is ongoing. Viking activity in the Iberian peninsula seems to have begun around the mid-ninth century as an extension of their raids on and establishment of bases in Frankia in the earlier ninth century, but although Vikings may have over-wintered there, there is as yet no evidence for trading or settlement. The most prominent and probably most significant event was a raid in 844, when Vikings entered the Garonne and attacked Galicia and Asturias. When the Vikings attacked A Coruña they were met by the army of King Ramiro I and were heavily defeated. Many of the Vikings' casualties were caused by the Galicians' ballistas powerful torsion-powered projectile weapons that looked rather like giant crossbows. 70 of the Vikings' longships were captured on the beach and burned. They then proceeded south, raiding Lisbon and Seville. This Viking raid on Seville seems to have constituted a significant attack. 859–861 AD saw another spate of Viking raids, apparently by a single group. Despite some elaborate tales in late sources, little is known for sure about these attacks. After unsuccessful raids on both northern Iberia and al-Andalus, the Vikings seem also to have raided other Mediterranean targets. Evidence for Viking activity in Iberia vanishes after the 860s, until the 960s-70s, when a range of sources including Dudo of Saint-Quentin, Ibn Ḥayyān, and Ibn Idhārī, along with a number of charters from Christian Iberia, while individually unreliable, together afford convincing evidence for Viking raids on Iberia in the 960s and 970s. Tenth- or eleventh-century fragments of mouse bone found in Madeira, along with mitocondrial DNA of Madeiran mice, suggests that Vikings also came to Madeira (bringing mice with them), long before the island was colonised by Portugal. Quite extensive evidence for minor Viking raids in Iberia continues for the early eleventh century in later narratives (including some Icelandic sagas) and in northern Iberian charters. As the Viking Age drew to a close, Scandinavians and Normans continued to have opportunities to visit and raid Iberia while on their way to the Holy Land for pilgrimage or crusade, or in connection with Norman conquests in the Mediterranean. Key examples in the saga literature are Sigurðr Jórsalafari (king of Norway 1103-1130) and Røgnvaldr kali Kolsson (d. 1158).

The Viking raid on Seville, then part of the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba, took place in 844. After raiding the coasts of Spain and Portugal, a Viking fleet arrived in Seville through the Guadalquivir on 25 September, and took the city on 1 or 3 October. The Vikings pillaged the city and the surrounding areas. Emir Abd ar-Rahman II of Córdoba mobilised and sent a large force against the Vikings under the command of the hajib (chief-minister) Isa ibn Shuhayd. After a series of indecisive engagements, the Muslim army defeated the Vikings on either 11 or 17 November. Seville was retaken, and the remnants of the Vikings fled Spain. After the raid, the Muslims raised new troops and built more ships and other military equipment to protect the coast. The quick military response in 844 and the subsequent defensive improvements discouraged further attacks by the Vikings. Historians such as Hugh N. Kennedy and Neil Price contrast the rapid Muslim response during the 844 raid, as well as the organization of long-term defences, with the weak responses by the contemporary Carolingians and Anglo-Saxons against the Vikings.

The Viking fleet, composed of allies of Hastein and Björn Ironside, sailed from their base at Noirmoutier on the Loire river estuary in Francia. Prior to attacking Seville, it was seen near the coast of France and on French rivers (the Seine, the Loire, and the Garonne). They plundered Asturias, under the rule of the Christian King Ramiro I, but suffered heavy losses at A Coruña and were defeated by Ramiro at the Tower of Hercules. Next, they sailed southward and plundered the Atlantic coast. They took the Muslim city of Lisbon in August or September of 844 and occupied it for 13 days, during which time they engaged in skirmishes with the Muslims. The governor of Lisbon, Wahballah ibn Hazm, wrote about the attack to Emir Abd ar-Rahman II of Córdoba, who was the overall leader of Muslims in Spain. After leaving Lisbon, they sailed further south and raided the Spanish towns of Cadiz, Medina Sidonia, and Algeciras, and possibly the Abbasid-controlled town of Asilah in Morocco.

On 25 September, the Vikings arrived near Seville after sailing up the Guadalquivir. They set up their base on Isla Menor, a defensible island on the Guadalquivir Marshes. On 29 September, local Muslim forces marched against the Vikings but were defeated. The Vikings took Seville by storm on 1 or 3 October after a brief siege and heavy fighting. They looted and pillaged the city, and, according to Muslim historians, gave its inhabitants the "terrors of imprisonment or death" and spared "not even the beasts of burden". Although the unwalled city of Seville was taken, its citadel remained in Muslim hands. The Vikings tried but failed to burn the city's recently-built great mosque.

When he heard about the fall of Seville, Abd ar-Rahman II mobilized his forces under the leadership of his hajib, Isa ibn Shuhayd. He summoned nearby governors to gather their men. They assembled in Córdoba, and then marched to Axarafe, a hill near Seville, where Isa ibn Shuhayd set up his headquarters. A contingent led by Musa ibn Musa al-Qasi, the leader of the semi-independent Banu Qasi principality to the north, joined this army despite Musa ibn Musa's political rivalry with Abd ar-Rahman, and played an important part in the campaign. In the following days, the two sides clashed multiple times, with varying results. Finally the Muslims won a major victory on 11 or 17 November at Talyata. According to Muslim sources, 500 to 1000 Vikings were killed and 30 Viking ships were destroyed. The Muslims made use of Greek Fire. The Muslims also reported that the commanders of the Vikings were killed and at least 400 were captured many of whom were hanged from the palm-trees of Talyata. The remaining Vikings retreated to their vessels and sailed downriver while the inhabitants of the surrounding countryside pelted them with stones. Soon, the Vikings offered to trade the plunder and prisoners they had taken in exchange for clothes, food, and unhindered downriver journey. After that, they rejoined the rest of the fleet on the coast. The weakened fleet, pursued by Abd ar-Rahman's ships, left the Iberian Peninsula after a brief raid in the Algarve.

The city of Seville and its suburbs were left in ruins. The destruction caused by the Viking raiders terrified the people of Al-Andalus. Abd ar-Rahman ordered new measures to guard against further raids. He established a naval arsenal in Seville and built walls around the city and other settlements. Ships and weaponry were made, sailors and troops were raised, and messenger networks were established to spread information about future attacks. These measures were successful in frustrating later Viking raids in 859 and 966. Most of the Vikings sailed back to Francia, and their defeat by the Andalusian army might have discouraged them from attacking the Iberian Peninsula again. The following year, the Vikings sent an embassy to the court of Abd ar-Rahman, who then sent the poet Yahya ibn al-Hakam (nicknamed Al-Ghazal, "the Gazelle") as an ambassador to the Vikings. Later Islamic sources report that some of the raiders remained and settled in the area, converted to Islam, and became cheese traders.

Evidence for Viking activity in Iberia after 861 is sparse for nearly a century: a range of sources including Dudo of Saint-Quentin, Ibn Ḥayyān, and Ibn Idhārī, along with a number of charters from Christian Iberia, together afford convincing evidence for Viking raids on Iberia in the 960s and 970s. The Chronicle of Sampiro and a number of later sources portray a raid in 968 led by one Gundered: a fleet of a hundred ships of Norsemen and Flemings arrives at the port of Iuncaria, intending to pillage Iria, but the Vikings are met at Fornelos by the armies of Bishop Sisnando Menéndez, who is killed in the battle. After three years devastating and pillaging the land, they are defeated at the Cebreiro mountains by one Gonzalo Sánchez, either a Galician count, Gonzalo Sánchez, or, according to some authors, as William Sánchez of Gascony. Bishop Sisnando was responsible for the fortification of Santiago de Compostela, allegedly against the raids of Norse, Flemings, and other enemies who uses to raid the lands and shores of Galicia. Several Galician charters of later decades relate the destruction of monasteries and the suffering of the people as "dies Lordemanorum" ("day of the Northmen"); in particular one charter dated in 996 uses the location of an ancient fortress of the Norse, in the south bank of the Ulla river, as a landmark. According to Ibn Idhārī, in 966 Lisbon was again raided by the Norse, this time with a fleet of 28 ships, but they were successfully repulsed. He recounts further raids in Al-Andalus, in a series of annalistic asides to narratives of events in Córdoba, for 971-72; these records chime with a note in the textually related, and not necessarily reliable, Anales Complutenses and the first group of the Anales Toledanos saying that Vikings attacked Campos (Santiago or to the Campos Goticos in the province of Leon) in 970.

Around 860, Ermentarius of Noirmoutier and the Annals of St-Bertin provide contemporary evidence for Vikings based in Frankia proceeding to Iberia and thence to Italy. Three or four eleventh-century Swedish Runestones mention Italy, memorialising warriors who died in 'Langbarðaland', the Old Norse name for southern Italy (Langobardia Minor). It seems clear that rather than being Normans, these men were Varangian mercenaries fighting for Byzantium. Varangians may first have been deployed as mercenaries in Italy against the Arabs as early as 936. Later several Anglo-Danish and Norwegian nobles participated in the Norman conquest of southern Italy. Harald Sigurdsson (c. 1015 –1066), given the epithet Hardrada ("stern counsel" or "hard ruler") in the sagas, was King of Norway (as Harald III) from 1046 to 1066. In addition, he unsuccessfully claimed the Danish throne until 1064 and the English throne in 1066. Before becoming king, Harald had spent around fifteen years in exile as a mercenary and military commander in Kievan Rus' and of the Varangian Guard in the Byzantine Empire. In 1038, Harald joined the Byzantines in their expedition to Sicily, in George Maniakes's (the sagas' "Gyrge") attempt to reconquer the island from the Muslim Saracens, who had established the Emirate of Sicily on the island. During the campaign, Harald fought alongside Norman mercenaries such as William Iron Arm. According to Snorri Sturluson, Harald captured four towns on Sicily. In 1041, when the Byzantine expedition to Sicily was over, a Lombard - Norman revolt erupted in southern Italy, and Harald led the Varangian Guard in multiple battles. Harald fought with the Catepan of Italy, Michael Dokeianos with initial success, but the Normans, led by their former ally William Iron Arm, defeated the Byzantines in the Battle of Olivento in March, and in the Battle of Montemaggiore in May. After the defeat, Harald and the Varangian Guard were called back to Constantinople, following Maniakes' imprisonment by the emperor and the onset of other more pressing issues. Harald and the Varangians were thereafter sent to fight in the southeastern European frontier as the Balkan peninsula in Bulgaria, where they arrived in late 1041. There, he fought in the army of Emperor Michael IV in the Battle of Ostrovo of the 1041 campaign against the Bulgarian uprising led by Peter Delyan, which later gained Harald the nickname the "Bulgar-burner" (Bolgara brennir) by his skald. Edgar the Ætheling, who left England in 1086, went there, Jarl Erling Skakke won his nickname after a battle against Arabs in Sicily. On the other hand, many Anglo-Danish rebels fleeing William the Conqueror, joined the Byzantines in their struggle against Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, in Southern Italy.

Björn Ironside was a historical Swedish Viking chief who also figures in late sources as a son of Ragnar Lodbrok and a legendary king of Sweden. He lived in the 9th century, being securely dated between 855 and 858. Björn Ironside is said to have been the first ruler of the Swedish Munsö dynasty. In the early 18th century, a barrow on the island of Munsö was claimed by antiquarians to be Björn Järnsidas hög or Björn Ironside's barrow. Medieval sources refer to Björn Ironside's potential sons and grandsons, including Erik Björnsson and Björn at Haugi. His descendants in the male line supposedly ruled over the Swedes until c. 1060. The complicity of Björn in all this is unclear. However, a number of Frankish, Arab and Irish sources mention a large Viking raid into the Mediterranean in 859-861 where he was supposedly involved. After raiding down the Iberian coast and fighting their way through Gibraltar, the Norsemen pillaged the south of France, where the fleet stayed over winter, before landing in Italy where they captured the city of Pisa. Flush with this victory and others around the Mediterranean (including in Sicily and North Africa) during the Mediterranean expedition, the Vikings are recorded to have lost 40 ships to a storm. They returned to the Straits of Gibraltar and, at the coast of Medina-Sidonia, lost 2 ships to fire catapults in a surprise raid by Andalusian forces, leaving only 20 ships intact. The remnants of the fleet came back to French waters in 862. Björn Ironside was the leader of the expedition according to the later chronicle of William of Jumièges. The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland say that two sons of Ragnall mac Albdan (Ragnar Lodbrok?), a chief who has been expelled from Lochlann by his brothers and stayed in the Orkney Islands, headed the enterprise. William of Jumièges refers to Björn as Bier Costae ferreae (Ironside) who was Lotbroci regis filio(son of King Lodbrok). William's circumstantial account of the Mediterranean expedition centers around Björn's foster-father Hastein. The two Vikings conducted many (mostly successful) raids in France. Later on Hastein got the idea to make Björn the new Roman Emperor and led a large Viking raid into the Mediterranean together with his protegée. They proceeded inland to the town of Luna, which they believed to be Rome at the time, but were unable to breach the town walls. To gain entry a tricky plan was devised: Hastein sent messengers to the bishop to say that, being deathly ill, he had a deathbed conversion and wished to receive Christian sacraments and/or to be buried on consecrated ground within their church. He was brought into the chapel with a small honor guard, then surprised the dismayed clerics by leaping from his stretcher. The Viking party then hacked its way to the town gates, which were promptly opened letting the rest of the army in. When they realised that Luna was not Rome, Björn and Hastein wished to invest this city but changed their minds when they heard that the Romans were well prepared for defense. After returning to West Europe, the two men parted company. Björn was shipwrecked at the English coast and barely survived. He then went to Frisia where he died.There are some historical problems with this account. Hastein appears in the contemporary sources later than Björn and could hardly, for chronological reasons, be his foster-father. Moreover, Luni is known to have been plundered by Saracens rather than by Vikings.

Πηγή : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Björn_Ironside

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viking_expansion

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vikings_in_Iberia

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harald_Hardrada

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viking_raid_on_Seville