The Proto-Slavic homeland is the area of Slavic settlement in Central and Eastern Europe during the first millennium AD. Traditionally, scholars put it in the marshes of Ukraine, alternatively between the Bug and the Dnieper, however, according to F. Curta, the homeland of the southern Slavs mentioned by 6th-century writers was just north of the Lower Danube. Little is known about the Slavs before the 5th century, when they began spreading in all directions. Jordanes, Procopius and other late Roman authors provide the probable earliest references to southern Slavs in the second half of the 6th century. Procopius described the Sclaveni and Antes as two barbarian peoples with the same institutions and customs since ancient times, not ruled by a single leader but living under democracy, while Pseudo-Maurice called them a numerous people, undisciplined, unorganized and leaderless, who did not allow enslavement and conquest, and resistant to hardship, bearing all weathers. They were portrayed by Procopius as unusually tall and strong, of dark skin and "reddish" hair, leading a primitive life and living in scattered huts, often changing their residence. Procopius said they were henotheistic, believing in the god of lightning (Perun), the ruler of all, to whom they sacrificed cattle. They went into battle on foot, charging straight at their enemy, armed with spears and small shields, but they did not wear armour.

The Sclaveni (in Latin) or Sklavenoi (in Greek) were early Slavic tribes that raided, invaded and settled the Balkans in the Early Middle Ages and eventually became known as the ethnogenesis of the South Slavs. They were mentioned by early Byzantine chroniclers as barbarians having appeared at the Byzantine borders along with the Antes (East Slavs), another Slavic group. The Sclaveni were differentiated from the Antes and Wends (West Slavs); however, they were described as kin. Eventually, most South Slavic tribes accepted Byzantine suzerainty, and came under Byzantine cultural influence. The term was widely used as general catch-all term until the emergence of separate tribal names by the 10th century. The Byzantines broadly grouped the numerous Slav tribes living in proximity with the Eastern Roman Empire into two groups: the Sklavenoi and the Antes. The term referred specifically to Slavic mobile military colonists who settled as allies within the territories of the Byzantine Empire. Slavic military settlements appeared in the Peloponnese, Asia Minor, and Italy.

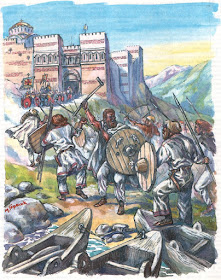

While archaeological evidences for a large scale migration are lacking, most present day historians claim that Slavs invaded and settled the Balkans in the 6th and 7th centuries. According to this dominant narrative, up until the late 560s their activity was raiding, crossing from the Danube, though with limited Slavic settlement mainly through Byzantine foederati colonies. The Danube and Sava frontier was overwhelmed by large-scale Slavic settlement in the late 6th and early 7th century. What is today central Serbia was an important geo-strategical province, through which the Via Militaris crossed. This area was frequently intruded by barbarians in the 5th and 6th centuries. From the Danube, the Slavs commenced raiding the Byzantine Empire from the 520s, on an annual basis, spreading destruction, taking loot and herds of cattle, seizing prisoners and taking fortresses. Often, the Byzantine Empire was stretched defending its rich Asian provinces from Arabs, Persians and others. This meant that even numerically small, disorganised early Slavic raids were capable of causing much disruption, but could not capture the larger, fortified cities.

Daurentius (fl. 577–579), the first Slavic chieftain recorded by name, was sent an Avar embassy requesting his Slavs to accept Avar suzerainty and pay tribute, because the Avars knew that the Slavs had amassed great wealth after repeatedly plundering the Balkans. Daurentius reportedly retorted that "Others do not conquer our land, we conquer theirs [...] so it shall always be for us", and had the envoys slain. Bayan then campaigned (in 578) against Daurentius' people, with aid from the Byzantines, and set fire to many of their settlements, although this did not stop the Slavic raids deep into the Byzantine Empire. In 578, a large army of Sclaveni devastated Thrace and other areas. In the 580s, the Antes were bribed to attack Sclaveni settlements. John of Ephesus noted in 581: "the accursed people of the Slavs set out and plundered all of Greece, the regions surrounding Thessalonica, and Thrace, taking many towns and castles, laying waste, burning, pillaging, and seizing the whole country." However, John exaggerated the intensity of the Slavic incursions since he was influenced by his confinement in Constantinople from 571 up until 579. Moreover, he perceived the Slavs as God's instrument for punishing the persecutors of the Monophysites. By the 580s, as the Slav communities on the Danube became larger and more organised, and as the Avars exerted their influence, raids became larger and resulted in permanent settlement. By 586, they managed to raid the western Peloponnese, Attica, Epirus, leaving only the east part of Peloponnese, which was mountainous and inaccessible. In 586 AD, as many as 100,000 Slav warriors raided Thessaloniki. The final attempt to restore the northern border was from 591 to 605, when the end of conflicts with Persia allowed Emperor Maurice to transfer units to the north. However he was deposed after a military revolt in 602, and the Danubian frontier collapsed one and a half decades later.

In 602, the Avars attacked the Slavic Antes; this is the last mention of Antes in historical sources. Chatzon led the Slavic attack on Thessaloniki that year. The Slavs asked the Avars for aid, resulting in an unsuccessful siege (617). In 626, Sassanids, Avars and Slavs joined forces and unsuccessfully besieged Constantinople. During the same year of the siege, the Sclaveni used their monoxyla ships in order to transport the 3,000 troops of the allied Sassanids across the Bosphorus which the latter had promised the khagan of the Avars. In 630, Sclaveni attempted to take Thessaloniki again. Traditional historiography, based on DAI, holds that the migration of Croats and Serbs to the Balkans was part of a second Slavic wave, placed during Heraclius' regin. Constans II conquered Sklavinia in 657–658, "capturing many and subduing", and settled captured Slavs in Asia Minor; in 664–65, 5,000 of these joined Abdulreman ibn Khalid. Perbundos, the chieftain of the Rhynchinoi, a powerful tribe near Thessaloniki, planned a siege on Thessaloniki but was imprisoned and eventually executed after escaping prison; the Rhynchinoi, Strymonitai and Sagoudatai Slavic tribes made common cause, rose up and laid siege to Thessaloniki for two years (676–678). Justinian II (r. 685–695) settled as many as 30,000 Slavs from Thrace in Asia Minor, in an attempt to boost military strength. Most of them however, with their leader Neboulos, deserted to the Arabs at the Battle of Sebastopolis in Caucasus in 692. Military campaigns in northern Greece in 758 under Constantine V prompted a relocation of Slavs under Bulgar aggression; again in 783. The Bulgars had by 773 cut off the communication route, the Axios valley in Macedonia, between Serbia and the Byzantines. The Bulgars were defeated in 774, after Emperor Constantine V learnt of their planned raid. In 783, a large Slavic uprising took place in the Byzantine Empire, stretching from Macedonia to the Peloponnese, which was subsequently quelled by Byzantine patrikios Staurakios (fl. 781–800). Dalmatia, inhabited by Slavs in the interior, at this time, had firm relations with Byzantium. In 799, Akameros, a Slavic archon, participated in the conspiracy against Empress Irene of Athens.

Byzantine literary accounts (i.e., John of Ephesus, etc.) mention the Slavs raiding areas of Greece during the 580s. According to later sources such as The Miracles of Saint Demetrius the Drougoubitai, Sagoudatai, Belegezitai, Baiounetai, and Berzetai laid siege to Thessaloniki in 614–616. However, this particular event was actually of local significance. A combined effort of the Avars and Slavs two years later also failed to take the city. In 626, a combined Avar, Bulgar and Slav army besieged Constantinople. The siege was broken, which had repercussions upon the power and prestige of the Avar khanate. Slavic pressure on Thessaloniki ebbed after 617/618, until the Siege of Thessalonica (676–678) by a coalition of Slavic tribes of Rynchinoi, Sagoudatai, Drougoubitai and Stroumanoi attacked. This time, the Belegezites also known as the Velegeziti did not participate and in fact supplied the besieged citizens of Thessaloniki with grain. It seems that the Slavs settled on places of earlier settlements and probably merged later with the local populations of Greek descent to form a mixed Byzantine-Slavic communities. The process was stimulated by the conversion of the Slavic tribes to Orthodox Christianity on the Balkans, during the same period.

Relations between the Slavs and Greeks were probably peaceful apart from the (supposed) initial settlement and intermittent uprisings. Being agriculturalists, the Slavs probably traded with the Greeks inside towns. Furthermore, the Slavs surely did not occupy the whole interior or eliminate the Greek population; Greek villages continued to exist in the interior. Some villages were probably mixed, and a degree of Hellenization of the Slavs by the Greeks of the Peloponnese had already begun during this period. When the Byzantines were not fighting in their eastern territories, they were able to slowly regain imperial control. This was achieved through its theme system, referring to an administrative province on which an army corps was centered, under the control of a strategos ("general"). The theme system first appeared in the early 7th century, during the reign of the Emperor Heraclius, and as the Byzantine Empire recovered, it was imposed on all areas that came under Byzantine control. The first Balkan theme created was that in Thrace, in 680 AD. By 695, a second theme, that of "Hellas" (or "Helladikoi"), was established, probably in eastern central Greece. Subduing the Slavs in these themes was simply a matter of accommodating the needs of the Slavic elites and providing them with incentives for their inclusion into the imperial administration.

From themes in Greece, Byzantine laws and culture flowed into the interior. By the end of the 9th century most of Greece was culturally and administratively Greek again, with the exception of a few small Slavic tribes in the mountains such as the Melingoi and Ezeritai. Although they were to remain relatively autonomous until Frankish Crusadors times, such tribes were the exception rather than the rule. Many Slavs were moved to other parts of the empire, such as Anatolia and made to serve in the military. In return, many Greeks from Sicily and Asia Minor were brought to the interior of Greece, to increase the number of defenders at the Emperor's disposal and dilute the concentration of Slavs. Even non-Greeks were transferred to the Balkans, such as Christian Armenians. As more of the peripheral territories of the Byzantine Empire were lost in the following centuries, e.g., Sicily, southern Italy and Asia Minor, their Greek-speakers made their own way back to Greece. Byzantine imperial rule support Greeks through population transfers and cultural activities of the Church was successful suggests Slavs found themselves in the midst of many Greeks. It is doubtful that such large number could have been transplanted into Greece in the 9th century; thus there surely had been many Greeks remaining in Greece and continuing to speak Greek throughout the period of Slavic migration. The success of suporting Hellenism in Greece also suggests the number of Slavs in Greece was far smaller than the numbers found in the northern Balkans (Illyria - Yugoslavia and Thrace - Bulgaria).

The Slavs, known as the Sklavenoi, migrated in successive waves. Small numbers might have moved down as early as the 3rd century however the bulk of migration did not occur until the 7th century. The Slavs migrated from Central and Eastern Europe and eventually became to be known as South Slavs . Most still remained subjects of the Roman Empire. The local Romans and Romanized remnants of the Iron Age populace of the Balkans began their assimilation into mainly the Slavs and Greeks, however, notable Latin-speaking communities are known to have survived. In literature, these Romance-speakers are known as "Vlachs". In Dacia, Roman colonists and Romanized Dacians retreated in the Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania after the Roman withdrawal. Archaeological evidence indicate a Romanized population in Transylvania by at least the 8th century. By the 7th and 8th centuries, the Roman Empire existed only south of the Danube River in the form of the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople. In this ethnically diverse closing area of the Roman Empire, Vlachs were recognized as those who spoke Latin, the official language of the Byzantine Empire used only in official documents, until the 6th century when it was changed to the more popular Greek. These original Vlachs probably consisted of a variety of ethnic groups (Thracians, Dacians) who shared the commonality of having been assimilated in language and culture of the Roman Empire with the Roman colonists settled in their areas. Anna Comnene relates in Alexiade about Dacians (instead of Vlachs) from Balkans and from the North side of Danube. Romance-speaking populations survived on the Adriatic mainly as Dalmatians , and the Albanians are believed by some to be descending from partially Romanized Illyrians.

The South Slavs (Balkan Slavs) are a subgroup of Slavic peoples who speak the South Slavic languages. They inhabit a contiguous region in the Balkan Peninsula and the eastern Alps, and in the modern era are geographically separated from the body of West Slavic and East Slavic people by the Romanians, Hungarians, and Austrians in between. Most notable are Serbs, Croats and Bulgarians. Southern-Slavic populations are genetically distinct from their northern linguistic relatives due to mixing with ancient indigenous populations of Illyrians, Latin and Greek speaking Thracians and Greeks. By the 580s, as the Slav communities on the Danube became larger and more organized, and as the Avars exerted their influence, raids became larger and resulted in permanent settlement. Most scholars consider the period of 581-584 as the beginning of large scale Slavic settlement in the Balkans. F. Curta points out that evidence of substantial Slavic presence does not appear before the 7th century and remains qualitatively different from the "Slavic culture" found north of the Danube. Byzantine re-assertion of the Danube defence in the mid-6th century and thereby lesser pillage yield amidst external threats resulted in political and military mobilisation and the itinerant form of agriculture may have encouraged micro-regional mobility. 7th-century archaeological sites shows earlier hamlet collections evolving into larger communities with differentiated designated areas (for public feasts, craftmanship, etc.). It has been suggested that the Sclaveni were the ancestors of the Serbo-Croatian group while the Antes were that of the Bulgarian Slavs, with much mixture in the contact zones. The diminished pre-Slavic inhabitants (including also Romanized native peoples) fled Barbarian invasions and sought refuge inside fortified cities and islands, whilst others fled to remote mountains and forests and adopted a transhumant lifestyle. The Romance-speakers within the fortified Dalmatian city-states managed to retain their culture and language for a long time. The numerous Slavs mixed with and assimilated the descendants of the indigenous population (Romanized Thracians and Illyrians and some Greeks). The scattered Slavs in Greece, the Sklavinia, were Hellenized. Romance-speakers lived within the fortified Dalmatian city-states. The migration of Serbs and Croats to the Balkans was part of a second Slavic wave, placed during Byzantine Emperor Heraclius' reign.

Πηγή : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sclaveni

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Balkans

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Slavs

Πηγή : https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sclaveni

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Balkans

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Slavs

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου